During World War II, my great-great grandmother Dessie Dulaney Mott, along with her daughter Wilma Dulaney Simkins, worked at the Green River Ordnance Plant near Amboy, Illinois. The munitions plant was situated about 30 miles outside of her residence in LaMoille.

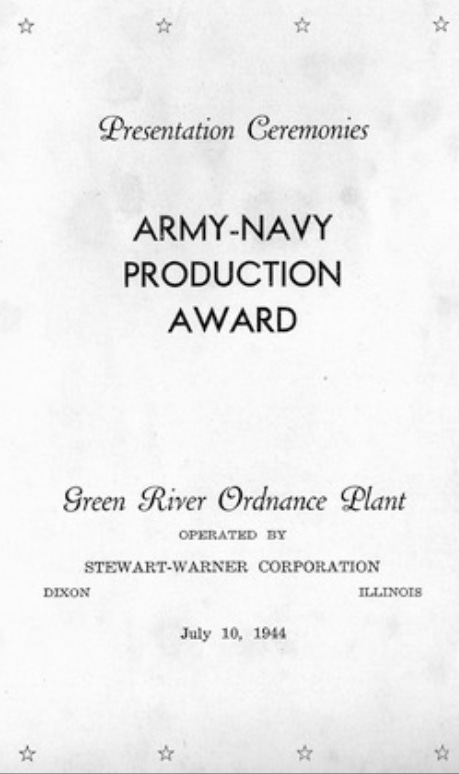

Dessie received two citations for excellence during her tenure, including an “E” pin, which she treasured. She also kept the program of the presentation ceremonies from July 10, 1944.

A real-life “Rosie the Riveter,” Dessie was one of the many women who worked on the front lines of the war production efforts during World War II.

History of the “E” Award

The Navy instituted an award for excellence in 1906, known as the Navy “E,” initially for excellence in gunnery. Over the years, it was extended to outstanding performance in communications and engineering, then eventually to plants producing war equipment during the 1940s. The Army-Navy Production Award was born from those efforts to recognize the “exceptional performance” on the production front.

Building bazooka rockets

Thanks to a letter written by Wilma Simkins to her granddaughter Rachael during the 1980s, I have a detailed account of what Dessie experienced while working at the Green River Ordnance Plant. And that included building bazooka rockets.

Your great grandmother [Dessie] Mott signed for the munitions plant as soon as it was started up in Amboy. She traveled the 30 miles daily either by bus or car pool. She continued there until the war was over and the plant closed. She worked 3 shifts. Your Dad was about 2 yrs old at the time. Grandma Mott worked on the Rocket Line. It was line 7. She worked almost all areas of the job from unpacking materials off railroad cars to the finished crated rocket. These rockets were called “Bazookas.” On the firing line in the war, they were ignited, dropped in some kind of apparatus and the firing mechanism propelled them many feet into the air in an arc to the target. The powder used in the munition was the one that caused the hair and skin to be orange tinged. Gram Mott had black hair but around the edge of her protective work cap she got the orange tinge. I do not know the size of this rocket but it had a nose cone and a long cylinder type body with a fuse detonator. The rocket ran on a conveyor from a work area called a “bay” to each area where different degree of work was done. The cones were staked on 2 sides. That was done manually as the body of the rocket rotated slowly. Then it was conveyed to another bay area. When it came to the fuse detonator area where the explosive was pressed in by machine, there precaution was utmost. A bricked metal plated area was built, the conveyer passing through it just open enough for it to pass. Workers had bullet proof glass windows to see their work and used robot handles to place the powder and fuse. The work was cautious. During the years it was used, there was just one explosion. The TNT fuse exploded setting off the powder killing one lady injuring 6. This happened on the shift just before Gram Mott went to work. She was on the same job. She said quite of few people refused to do the job after it was rebuilt, but many said “well the young boys are being killed on the field, we can or should be as brave and continue the job” and they did.

Gram Mott met many ladies her age from all parts of the area. Dixon, Sublette, Mendota, Sterlin Rockfalls Ill. She corresponded with them through the years after. She always mentioned several Indian ladies from an Indian reservation in South Dakota. They lived in a mobile home court near the plant and worked. They had sons in the service. They were good workers and good ladies.

Producing 52mm projectiles

Wilma also worked at the plant, for about 3-4 months, and described the strenuous work she endured.

I was home with small children but was needed for production in the munitions. Neighbor ladies that weren’t able to work and your great grandmother Simkins agreed to help with the baby sitting. There was a bus from Depue to the Defense plant a 50 mile trip. I worked the three shifts. My line was #1. We produced the 52 Mlmeter shells. The casings weighed 12 ½ lbs a piece as they came off the railroad cards to the conveyor. I worked from that area to the crating of the finished shell. Many steel splinters were stuck in my hands and aching shoulder muscles at the end of a shift. As they shells moved along from bay to bay by conveyor, different processes were done. Nose cones were staked on, powder poked in the body of the shell, and a detenator packed with explosive powder and then screwed into the end of the shell. Next a brass body screwed on the end of the shell, the 52 ml.meter shell body was approx. 12 inches long and 5 inches diameter. The nose cone was about 5 inches long and the brass body 24 inches long. As far as I know there was never an explosive accident on that line. I believe the most difficult job for the women on this line was the crating. Rough lumber was used. We had to hammer nails to hold the shells in this crate. This crating was called a Clover leaf.

Below are sketches that Wilma included with her letter.

Daily life at the Green River Ordnance Plant

Wilma’s letter also painted a vivid picture of what life was like for workers at the Green River Ordnance Plant during World War II.

You had to wear an identification badge and your picture was on it. No badge. No enter. Then you had to go to the main office, prove who you were by their registration given a temporary badge, then go to your line. You lost time on your paycheck having to go through that procedure. On entering your particular line (you were assigned as you were accepted for a job) Oh yes you were fingerprinted and investigated before you got a job. On entering your line, immediately to the change house, you disrobed all except your underclothes which had to be cotton even hosiery. (because of friction sparkes on nylon polyester etc) You were given a cotton pair of coveralls and a cotton cap. Your hair had to go up under the cap. No hair pins or combs (sparks). If you had to have a sweater, of course all cotton. The shoes were a composition sole that would not cause static electricity as you walked. These were furnished by the plant. There were several buildings (metal) consisting of the line. Each building a different part of the munitions line. As a rule no one ever worked on another line except to what you were assigned. There was a very nice cafeteria on each line - food good reasonable priced. If you brought a lunch bucket or sack lunch it had to be taken to a locker inspected by a guard as you went by him. Sabotage you know. Once every month after completing so many units of munitions the buildings and machinery were hosed down, it was supposed to warm water more usually cold, even during the winter months. Every one had to sweep or mop and wipe machinery Every one hated it. The buildings were immense and cold in winter. The powder used in the munitions was different for different types. The amount of T.N.T. and chemistry of the TNT would cause different degrees of headaches and nausea. Some of it caused the hair to turn orange, skin even tinged. Another line might cause a greenish blue tinge. TNT was nitroglycerine that’s what causes explosion.

At the end of the shirt (3 shifts) (8 AM - 4PM – 4 PM - 12 AM – 12 AM - 8 AM) ladies + men separate you had to go to the change house. In one large room every one disrobed - all outer wear was put in huge hampers, under clothes were removed (personal) and put in a separate bag to take home. You had to have a clean change to wear home. Every one had to shower and use soap. Could bring your own shampoo or wear shower cap and then shampoo at home. The reason for this cleanliness was due to the effects, collected powder causing illness.

Every one that was able, any age 18 and up could apply for work. You were encouraged to help the war effort. Many people at that time had their first Social Security number. You had to pool your cars. Buses were encouraged. On using your car for work you were issued gas stamps and tire stamps only if you were using your car for a pool. You had to have proof of your riders. That business was a real pain because it was hard to have all that questioning. There was an office in offices in each county to go to for these stamps. Each family was allowed so many according to number in family sugar, shoes and shortening stamps. This was caused by so much of these materials being used by the armed services. No one complained. So many had brothers, fathers, or sons at war. The people that worked in defense plants or munitions had an easier time with stamps than others. It was pretty tight going even so, with the gas and foods. Families had to decide pretty drastically how much everyone got of the rationed articles. Many times one family that didn’t use certain stamps would trade them to another for something they needed. One often heard of counterfeiting of the stamps. Having a garden, raising chickens, or a hog helped many families. The gardens were called “Victory Gardens” because by their use, it helped the war effort.

The young men were automatically drafted into the service. The older family men were listed 1A-2A-or deferred, as their jobs qualified them. Some men the age to be drafted often opted to farm or get a job in defense so they could escape going to war. They were called “Draft Dodgers.”

Researching your ancestors who worked at the Green River Ordnance Plant

It’s important to note that most people who worked at the plant were not federal employees, so you’re unlikely to find personnel files in the National Archives. Most plant workers were contractors of the operating company, Stewart-Warner Corporation.

I recommend getting a copy of Duane Paulsen’s book Memories of the Green River Ordnance Plant 1942-1945. I’ve also discovered a collection of materials related to the plant at Northern Illinois University. The plant even had its own newspaper!

Green River News, 1943-1944, RHC-VFM-11-11.16a. Northern Illinois University. http://archives.lib.niu.edu/repositories/2/resources/685

Green River News, 1944-1945, RHC-VFM-11-11.16b OV. Northern Illinois University. http://archives.lib.niu.edu/repositories/2/resources/683

Green River Ordnance Plant Records (Amboy/Dixon), RHC-RC-295. Northern Illinois University. http://archives.lib.niu.edu/repositories/2/resources/479

I’ll be visiting NIU in late May to research these materials in person and hopefully find even more details about my relatives’ employment at the munitions plant.

This post was inspired by 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks.

Another very interesting read and info that I never knew about.

Always a fascinating story! Thank you!